Rathee's trilogy — CrypTFlow2, SIRNN, and SecFloat

Background

Notation: Let

Assume having the following basic knowledge in Multi-Party Computation:

- 1-out-of-

can be implemented using public-key cryptography or similar methods, with a communication cost of per instance; using IKNP, this can be reduced to . - Addition and scalar multiplication based on 2-party additive secret sharing are almost free (no communication overhead).

- Secure multiplication operations for 2-party computation can be implemented using Beaver triples. One secure multiplication operation requires a total communication cost of

.

For floating-point storage, we use IEEE 754 Float32 (single-precision standard):

-

-

Sign bit

1 bit, exponent 7 bits, mantissa 23 bits, -

Round-to-nearest-ties-to-even

IEEE 754 Addition

Without loss of generality, assume

The steps are as follows:

- Exponent alignment. If

, right-shift the mantissa of : . - Mantissa addition. Consider the signs of

and . If they have the same sign, calculate . If they have different signs, subtract the smaller from the larger to get the absolute value of the difference , and attach the correct sign . - Normalization. Clearly,

, so only needs to be right-shifted at most once (corresponding to adding 1 to the exponent ). If , skip directly to step 4. Otherwise, repeatedly left-shift and decrement until . - Write the result. Finally, remove the leading 1 of

, and use the final as the new 32-bit floating-point result. - Rounding issues may arise in the following four steps:

, , , and right-shifting by one bit.

IEEE 754 Multiplication

Multiplication is relatively simple because it doesn't involve comparing the magnitudes of numbers.

- XOR the sign bits.

. - Add the exponents.

. - Multiply the mantissas.

, the result is in the range . - Normalize. If the result

, increment and right-shift by one bit, then remove the most significant bit of . - Rounding operations are involved in the steps of

and right-shifting by one bit.

Rounding Method

Let

Simply put, a carry (

Note that normalization may be required after rounding.

Building Blocks

Below, we will explain how the entire protocol is constructed using a bottom-up approach.

The ideal function we need to implement is MUX(b,x)=(b==1?x:0). That is, for a Boolean secret share

SETUP:

and each generate random numbers . sets based on the value of . If , let , otherwise it is . acts as the sender and performs one round of 1-out-of-2 OT with . provides two messages , and provides and ultimately obtains . sets based on the value of . If , let , otherwise it is . - Another round of OT is performed, and

obtains . contributes , and contributes . The sum is .

We list four possible cases for

,

| 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 0 | 1 | |||

| 1 | 0 | |||

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

The result is exactly equal to

The communication cost is the overhead of two rounds of IKNP-OT, which is

This is a direct implementation with Beaver triples, the communication overhead is

We have

We divide

randomly selects and prepares messages for . uses these messages as input to the OT, inputs , and obtains . - If and only if

, we have , which completes the secure equality comparison of and .

We can extend the

The approach still involves block processing. First, we compute the result

Then, during the merging process, we prioritize the higher-order bits:

The communication cost is less than

Assume the LUT has

SETUP:

- For each

, constructs . performs a 1-out-of- with (who selects ) using these messages of length -bits each. The cost is . sets . Now holds , and holds . - In the online phase,

sends , and sends . Both parties simultaneously compute . Finally, and store and respectively, which together reconstruct . The communication cost of is negligible.

If we want to compute

randomly selects , generates the pair , and performs a 1-out-of-2 with (who holds input ). receives the result . sets . - Both parties perform local linear correction:

computes , and computes .

Let's verify the result:

- When

, , so . - When

, , so . But in this case, , so still holds.

The communication cost is one 1-out-of-2

Having already defined

However, since we are only performing a zero-extension operation, the sum of the two shares cannot produce a carry at the

The cost is

Since we have x >> s):

SETUP:

The cost is

writes its in binary as . - For

, a 1-out-of-2 is called: holds , holds , generating such that . - Both parties locally compute

. Clearly, the sum of the two shares is the product .

The total communication cost is

The semantics are that both parties hold

Here, we cannot directly use Beaver triples because they are ring-agnostic, which might lead to unknown wrap-around issues. One approach is to extend both

We now need to compute

- First, we need to consider whether

and overflow, so we need to detect and obtain two overflow bits . - Then we can use

to compute the shares of g=w_y?x:0andh=w_x:y:0, handling the possible overflow difference. - Finally,

outputs .

Let's try adding the two shares together:

And

Combining them,

Let

The principle of

The function is to split an

Of course, the solution to this problem is also straightforward. First, use

The complexity is equivalent to the cost of

The detection of the global index corresponding to the highest non-zero bit in the

I don't quite understand this point. The case where

can also be solved directly using without increasing communication costs.

In short, the communication volume is equivalent to a 1-out-of-

The former means determining whether a vector of length

These two can be implemented using 1-out-of-

The meaning is that given an input

- First, compute the input

using to obtain , then for each , call to obtain . - Call

to obtain Boolean shares , and use (i.e., Beaver triple) for any to compute . Thus, . The value of the most significant non-zero bit is the last one from largest to smallest that satisfies . - For the most significant digit, let

, and for the remaining , . - Finally, locally compute

, and call to obtain the final Boolean vector .

Summary

| Primitive | Dependent Primitives | Function | Communication Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ternary operator of length |

|||

| Logical OR | |||

| Arithmetic equality of length |

|||

| Arithmetic comparison of length |

|||

| Lookup table with |

|||

| Zero extension from |

|||

| Truncation of |

|||

| Unsigned/signed multiplication of length |

|||

| Index of the highest non-zero bit in a number of length |

Primitives

We have finally built all the basic protocols corresponding to the secfloat paper, and now we move on to the important primitives constructed in this paper.

This is used to check whether floating-point numbers overflow or underflow given floating-point parameters

α = (z, s, e, m)

if 1{e > 2^{p-1} - 1} then

m = 2^q; e = 2^{p-1}

if 1{z = 1} ∨ 1{e < 2 - 2^{p-1}} then

m = 0; e = 1 - 2^{p-1}; z = 1

Return (z, s, e, m)

This logic aligns with the paper's approach to handling overflows. Here's a brief description of how the protocol works:

- The second line involves a

operation because is public; the fourth line involves an operation. - The assignment operations in the third and fifth lines do not raise privacy concerns because the assignment constant

is public; therefore, and can be used directly. - The if-branch essentially represents the specific semantics of the

operation.

(x >> s) | (x & (2**s - 1) != 0). The right shift is handled by

Since

We first use TRS(x, r-2) to check if the bits after TR(x, 2) and add the rounding result

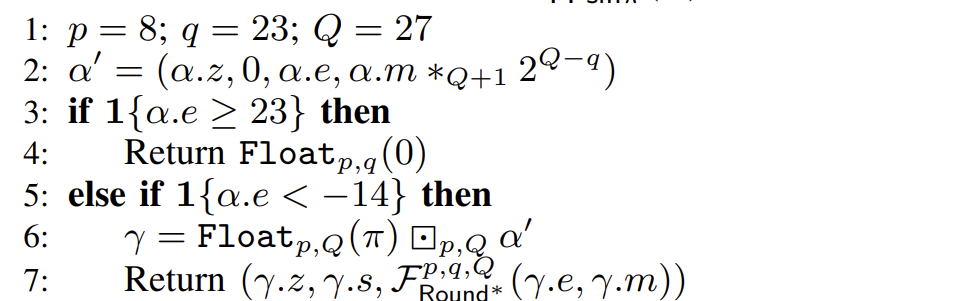

Given the floating-point number

if 1{m >= 2^{Q+1} − 2^{Q−q−1}} then

Return (e+1, 2^q)

else

Return (e, m >>R (Q−q))

The following explains the correctness of the code's logic. The mantissa is considered in two cases:

- First, when the first

bits of the mantissa are all 1s, and the -th bit (corresponding to ) is also 1. This exactly satisfies the minimum rounding condition of RNTE, so the entire bits will be rounded to 2.0. After normalization, , and the mantissa returns to its original -bit precision normalized form . - Second, in most cases where rounding does not require further normalization, simply perform a right shift of

bits with rounding according to the previous protocol.

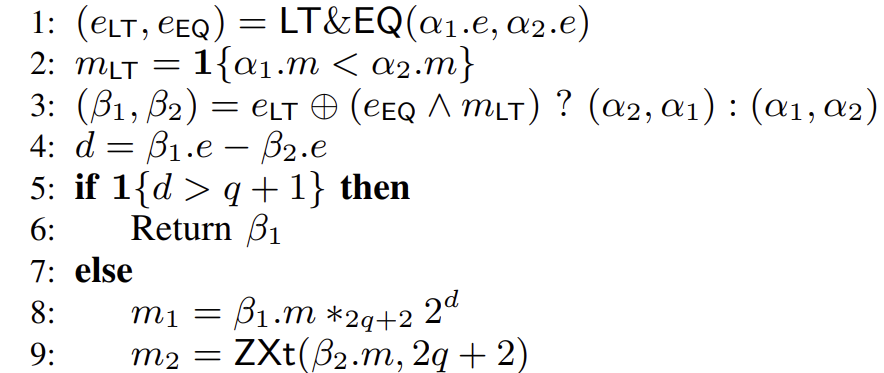

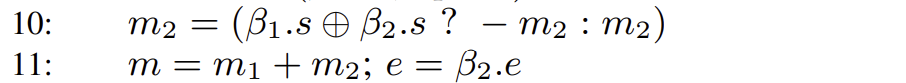

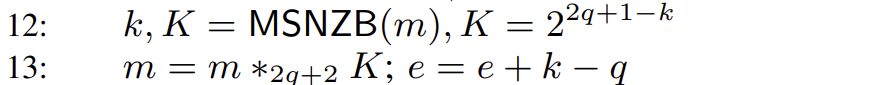

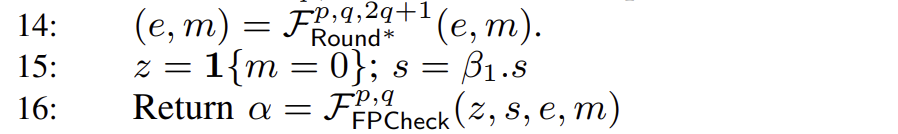

In the Background Chapter, we summarized the method for ordinary floating-point addition. Below, we will show how this method corresponds to pseudocode:

- Exponent alignment. If

> , left-shift the mantissa of : .

- Add the mantissas. Consider the signs of

and . If they have the same sign, calculate . If they have different signs, subtract the smaller one from the larger one to get the absolute value of the difference, , and attach the correct sign .

Here we consider the cases of same and different signs. When the signs are the same, the XOR of the sign bits of

- Normalization. Here we find the most significant bit in the sum

. To ensure sufficient space for rounding, the protocol zero-extends and , which have precision , to bits in the first step (but note that the precision is ). Assuming the result of MSNZB is , normalizing the most significant bit (i.e., aligning it with the bits used in the subsequent Round* protocol) requires a left shift of bits, corresponding to multiplication by .

Regarding the calculation of the exponent, since it was shifted left by

- Writing the result. Finally, a round of rounding is performed using

. Since , the sign bit is determined by . Finally, check if the normalized result is within the valid range of floating-point numbers.

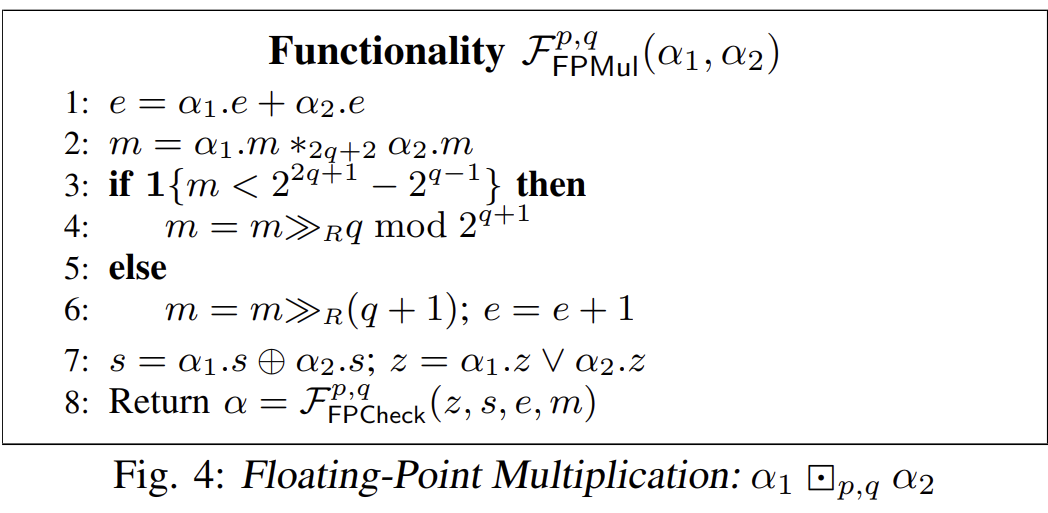

- XOR the sign bits.

. (Line 7) - Add the exponents.

. (Line 1, the paper sets here) - Multiply the mantissas.

, the result is in the range . (Line 2) - Normalization. If the result

, increment and right-shift by one bit, finally removing the most significant bit of .

If the result

, follow the elsebranch on line 6, otherwise follow theifbranch on line 4.

- Rounding operations are involved in the steps of

and right-shifting by one bit. (i.e., on lines 4 and 6)

Math Functions

In the book これでなっとく!数学入門――無限・関数・微分・積分・行列を理解するコツ written by 瀬山士郎, a following excerpt explained how to calculate trigonometric functions on computers/calculators (I don't have the English version of this book, so I summarized it using ChatGPT):

The pages explain how trigonometric functions, especially the sine function, are calculated. Through a short classroom dialogue, the text raises the question of how a calculator can produce a value such as

. It then explains that trigonometric functions cannot be represented by finite polynomials, but they can be expressed as infinite power series, known as Taylor (or Maclaurin) expansions. Using as an example, the book shows its series expansion and explains that by taking only the first few terms, one can obtain an approximate value of . The more terms used, the more accurate the result becomes. Although the series is infinite and never truly ends, calculators compute enough terms to achieve practical accuracy, which is sufficient for most real-world applications.

Based on this idea, we can actually elaborate on how a computer calculates

- First, use trigonometric identities to reduce the range of

to . (Range reduction)

This is the approach used in the paper, but in practice, rounding to

and then using the double-angle formula reduces the error by an order of magnitude.

- Use Taylor series expansion for approximation, for example,

. (Polynomial Evaluation) - Use Horner's method:

, to reduce the number of multiplications and lower the error.

These operations only require floating-point addition and multiplication. The coefficients of the polynomial are relatively fixed and can be obtained through a lookup table.

We now correspond this to the specific primitive function

- First, handle special cases: When

, since , it exceeds the precision of the mantissa, so must be an integer. Therefore, . Another special case is when , in which case , and the error is within the error of the floating-point representation of itself.

- Range Reduction Step: The goal is to calculate the parity bit

and the interval from the input . Let . If , then ; otherwise, . Therefore, .

m = α.m * 2^{α.e + 14}

a = TR(m, q+14); n = m mod 2^{q+14}

Transform

f = (n > 2^{q+13} ? 2^{q+14} - n : n)

k,K = MSNZB(f); f = f * K

z = 1{f=0}; e = (z ? -2^{p-1}+1 : k - q - 14)

The first line ensures that

When

δ = (z, 0, e, TR(f, q+14−Q))

Finally, the fixed-point number

- Polynomial Evaluation Step: Note that the paper uses the Remez method and other more accurate approximation methods, rather than Taylor expansion:

if 1{δ.e < −14} then

µ = Float_{p,Q}(π) ⊗_{p,Q} δ

Previously, in the special case where

if 1{δ.e < −5} then

idx1 = δ.e + 14 mod 2^4

(θ1, θ3, θ5) = GetC_{4,9,5,p,Q}(idx1, Θ1_sin, K1_sin)

Consider the case where K1_sin, it retrieves the corresponding parameters (θ1, θ3, θ5) from the table Θ1_sin using the index idx1 (which is the lower 4 bits of δ.e+14).

4 is the number of bits in the table, 9 is the number of splines (coefficient pairs), and 5 is the degree of the fitted polynomial.

idx2 = 32 · (δ.e + 5 mod 27)

idx2 = idx2 + ZXt(TR(δ.m, Q−5) mod 32, 7)

idx2 = 1{δ.e = −1} ? 127 : idx2

(θ1, θ3, θ5) = GetC_{7,34,5,p,Q}(idx2, Θ2_sin, K2_sin)

In the interval δ.e + 5 and the upper 5 bits of δ.m (this is the second innovation of the paper: segmented indexing) to call the corresponding (θ1, θ3, θ5) that minimizes the error. The case of

- Use the Horner's method to calculate the corresponding floating-point value:

Δ = δ ⊗_{p,Q} δ

µ = ((θ5 ⊗ Δ) ⊞* θ3) ⊗ Δ

µ = (µ ⊞* θ1) ⊗ δ

Return (µ.z, a ⊕ α.s, Round*(µ.e,µ.m))

As mentioned earlier, a ⊕ α.s determines the sign bit, and the final result is obtained by rounding.

To summarize, the

One potential drawback of this method is that the table used by the GetC function is ad-hoc and differs from the protocol used for floating-point arithmetic operations. If one wants to arbitrarily specify

Let

- If

, let , then , and . - If

, if , will approach zero, and the subtraction of two large numbers will affect the precision. Therefore, the author transforms the expression to . Let , then , and then calculate . This avoids the error problem caused by subtracting two numbers.

Then, two sets of approximate polynomials

Next, the value of

- Range Reduction Step:

a = 1{N = −1}

f = a ? (2^{q+1} − α.m) : (α.m − 2^q)

k,K = MSNZB(f); f = f *_{q+1} K

e = a ? (k − q − 1) : (k − q)

When

z = 1{f = 0}; e = (z ? −2^{p−1}+1 : e);

N = α.e; δ = (z,0,e, f *_{Q+1} 2^{Q−q})

A floating-point number

- Polynomial Evaluation Step:

if 1{δ.z} then

µ = Float_{p,Q}(0)

When

if 1{δ.e < −5} then

idx1 = (δ.e + 24) mod 2^5

(θa0,θa1,θa2,θa3) = GetC_{5,19,4,p,Q}(idx1, Θ1_log, K1_log)

(θb0,θb1,θb2,θb3) = GetC_{5,18,4,p,Q}(idx1, Θ3_log, K3_log)

When δ.e + 24 are used as the index to look up the table Θ1_log for the case Θ3_log for the case

else

idx2 = 16 · (δ.e + 5 mod 2^7)

idx2 = idx2 + ZXt(TR(δ.m, Q−4) mod 16, 7)

(θa0,θa1,θa2,θa3) = GetC_{7,20,4,p,Q}(idx2, Θ2_log, K2_log)

(θb0,θb1,θb2,θb3) = GetC_{7,32,4,p,Q}(idx2, Θ4_log, K4_log)

When δ.e + 5 and the upper 4 bits of δ.m as the index to look up the table Θ2_log for the case Θ4_log for the case

(θ0,θ1,θ2,θ3) = a ? (θa0,θa1,θa2,θa3) : (θb0,θb1,θb2,θb3)

Based on the classification of the value of

- Horner's method and the final addition of

.

µ = ((θ3 ⊗ δ) ⊞* θ2) ⊗ δ

µ = ((µ ⊞* θ1) ⊗ δ) ⊞* θ0

Calculate the value of the cubic polynomial

β = LInt2Float(N)

β′ = (β.z,β.s,β.e, β.m *_{Q+1} 2^{Q-6})

Using a small LUT (lookup table),

γ = a ? µ : (µ ⊞* β′)

Return (γ.z, γ.s, Round*(γ.e, γ.m))

Finally, a floating-point addition is performed:

- If

, then , - If

, then .

The final result of the protocol is obtained by rounding